If a man of 47 is offered a choice between wintering in the Antarctic and filling a post in a Moscow office he will, in all probability, do some serious thinking before reaching a decision.

A 17-year-old however, chooses the Antarctic straightaway — in seven cases of 10, including girls.

This is not an assumption, it is a fact. In the 1930s the majority of Soviet youngsters were "mad" about the Arctic and flights to the North Pole when our country was mastering the Arctic seas and the vast adjacent territories.

In the 1950s young people headed for the virgin lands. It was not a soft job, nor one for complainers or whiners to turn these immense waste steppelands of Northern Kazakhstan into cultivated fields. But it was a vital job for a country which from olden times has experienced winter- killing of crops, droughts and dust storms in summer.

It was natural that the mastering of the virgin lands was pioneered by members of the Komsomol (Young Kommunist League). Earlier this year the pioneers observed the 20th anniversary since the "first peg" was driven into the soil.

It was in Kazakhstan that the idea of youth building teams and top priority projects was conceived. Initially, they tackled the construction of needed public and service buildings on the new state farms which were suffering from a shortage of labour.

During the summer holidays students came from all over the country to help.

It became obvious that boys and girls of 17-19 were capable of transforming large investments — in one season — into socially useful structures. And they did it with songs, jokes, their own rules and self- government.

Logically, why not go further? Instead of merely summer jobs, the young people were offered a more substantial outlet for their energies — the construction of an entire economic project, from beginning to end.

Let us imagine that in the depths of Siberia there is an excellent site for the construction of a metallurgical plant. There is a rich deposit of iron ore, and power can soon be provided from a big station that was itself a top priority project in the previous five-year plan. All that is lacking is manpower to give impetus to the development of an enormous region. The normal employment office channels arc not good enough. Skilled workers have in the main settled down in their jobs and have no desire to pull up stakes

At the same time, in the settled areas of the country there is a huge pool of 17 to 20-year-olds with plenty of energy and ambition who are longing to go somewhere and do something — something important and significant that might even be written up in the newspapers.

Komsomol newspapers and magazines regularly carry features on top priority construction sites. There are the atomic power stations in Armenia, and beyond the Arctic Circle. In Turkmenia the spectacular irrigation projects will make the desert bloom. Siberia is now and will be in the t utu re the home of numberless projects that are gradually taming the proud wilderness.

In Moldavia the climate and work are of a different order: collective farms have been jointly planting orchards on an enormous scale. The Odessa-Kishinev train clips along in stretches for an hour or more beside row upon row of apple trees disappearing into the horizon.

On the banks of the Kama and Volga rivers motor-car and lorry plants are going into production — the promise of future abundance. As the factories rise, so do bustling, lively cities where the average age of the inhabitants is under 30.

Young men who have finished their two-year army stint often opt for the wilderness: they lay pipelines across swamps in Western Siberia, build railways in the primeval taiga or construct docks and piers on the stormy coasts of oceans and seas.

Or take Byelorussia. In recent years this republic has been more and more frequently asking young men and women to come and help build villages of a new type, well-planned and organised better than some cities and towns. Newspapers have given extensive coverage to Vertelishki, an experimental model of such a rural town. Photographs have shown the collective farm management building. with a clock tower. The sidewalks, made of concrete slabs, lead almost to the fields and the little houses look immensely attractive.

Of course, tht Byelorussians hope that some of the young comers, upon completing construction, will decide to remain to live and work in their land.

Generally speaking, this is expected whenever the Komsomol takes responsibility for a building project that is vital to the country or one of its constituent sovereign republics.

While the young volunteer builders are working on their construction project they are given courses in trades which will be needed on completion of the work.

Do many people thus settle down? That depends, but normally the proportion does not exceed 50 per cent Some, when the contract ends, move on in order to continue their education. Lads of 18 are called up for military service.

Nevertheless, the practice of toppriority Komsomol projects, with their atmosphere of youthful ardour, pure and sincere dedication to the job, justifies itself.

Every year many industrial agencies request the Komsomol Central Com mittee to designate this or that project a top priority one. The scheme which in essence is of a voluntary, public-spirited nature, yields sizeable economic benefits.

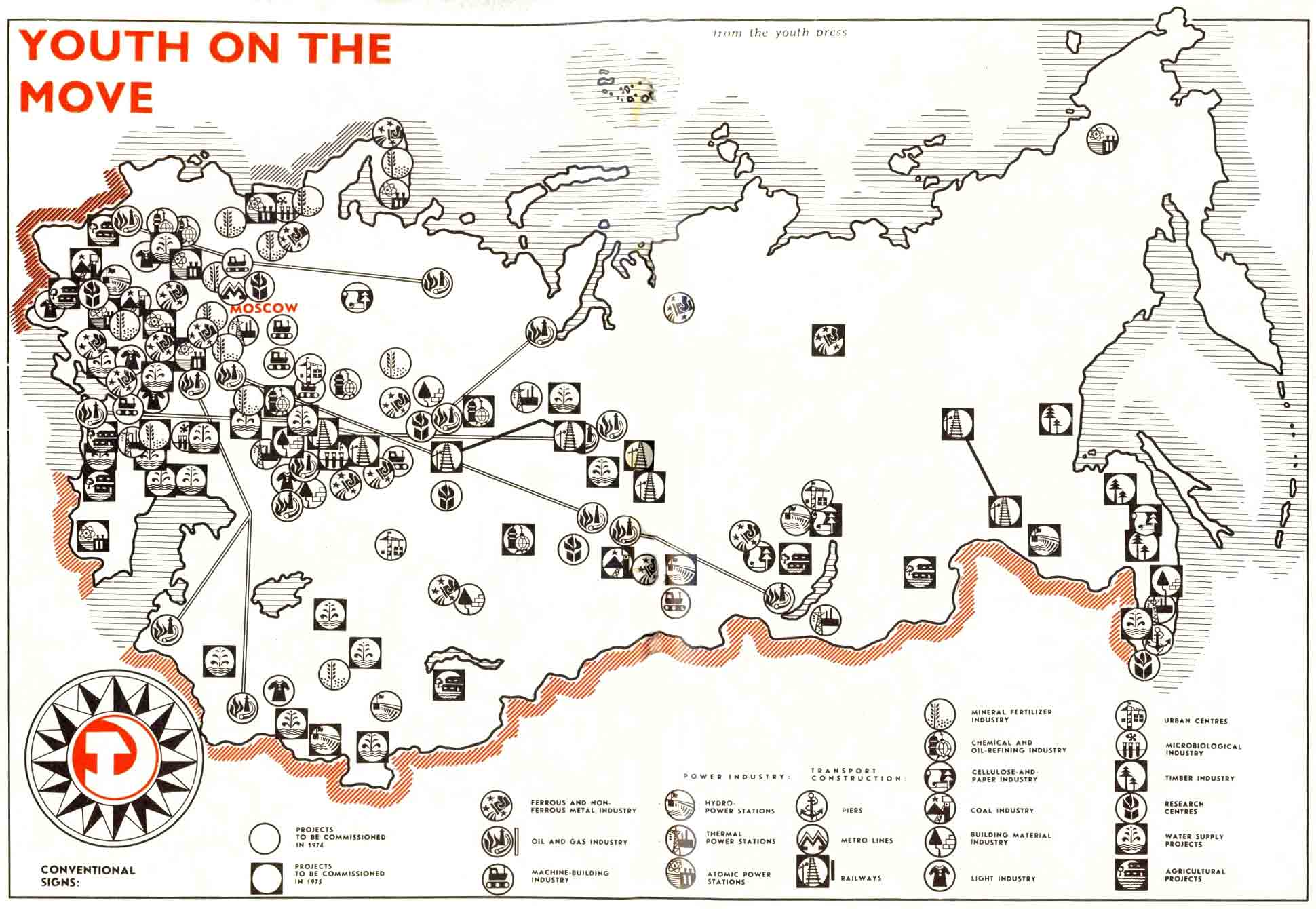

In 1974, 135 projects have been singled out as "all-union Komsomol projects" (see map). It is expected that by the middle of this year, when the secondary and vocational training schools have completed their final examinations, close to 80,000 young people will have left to carve out their future with a special "Komsomol assignment" in their pocket.

Sputnik. №5 May 1974